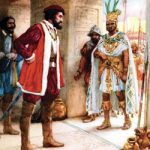

In Mexico City´s Palacio de Bellas Artes there is a large mural painted in 1950 by David Alfaro. La Tormenta de Cuauhtémoc depicts Cortés’s torture of the last Aztec emperor. This work has political and cultural significance. Alfaro’s mural is based on both legend and written historical fact as recorded by Bernal Díaz del Castillo in his book The Discovery and Conquests of Mexico. This book, written fifty years after the conquest, is the only firsthand account of Cortés’s physical, mental and religious struggles while trying to enrich both the Catholic Church and the coffers of the Spanish King, Juan Carlos. Bernal Díaz was a soldier who had previously sailed with the Grijalva expedition exploring the Yucatan. Diaz joined with Cortés in Cuba the same month he returned from the Grijalva voyage. Diaz fought alongside Cortés for nearly three years as the Spanish subjugated the Aztecs and later accompanied the Spanish conqueror as he explored today’s Guatemala and Honduras. This mural shows both Cuauhtémoc and his cousin Tetlepanquetal with their arms and legs bound, their feet, which had been covered in oil and placed onto burning faggots.

Another earlier painting of this same subject shows Cuauhtémoc and his cousin tied to rocks and their feet stretched over small flaming braziers. Both works leave out The Tlatoni of Tlacopan, a third person also tortured and subsequently hanged along with the cousins. Supposedly Cuauhtémoc turns to his cousin and says, “I´m not exactly lying on a bed of roses.” A quote that one would doubt except that it recurred in several different “histories” of the event. Cortés justified these cruelties because he suspected Cuauhtémoc of knowing where the Aztec gold was hidden and he also suspected the captive Cuauhtémoc of plotting another insurrection. It has been speculated that the Aztec gold objects had previously been melted down and turned into gold bars by the Spanish, had either been tossed into the muddy lake waters that surrounded the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, or as some claimed been sent to various hideouts by Montezuma. The mystery of what happened to the Aztec treasures has been the subject of much speculation, theories, books and movies.

In 1981, during the construction of a Mexico City subway line, one of the gold bars was discovered sixteen feet (five meters) underground. An estimated 8,000 pounds of gold and silver had been melted and stored in a room in the Aztec capital, ready for shipment to Spain.

Cortés did not discover Mexico so much as he explored and conquered it. He received permission to sail to Mexico from the governor of Cuba, where the widowed Cortés lived. His wife, who died of possible poisoning, was the sister of Cuba’s governor. A month after receiving permission, Cortés sailed from Cuba on February 18, 1519, 27 years after Columbus landed in Española. Cortés commanded 11 ships (which he later had burned to prevent malcontents from deserting), 508 soldiers, 100 sailors, 16 horses, and 14 small cannons. Cortés was not an ordinary man. He was motivated to take his place in history and possibly by greed. It took 32 months of fighting, negotiating, and a smallpox plague for Cortés to accomplish his goal of subjugating the Aztecs. He landed in the Aztec vassal state of Tabasco where the indigenous Toltec people were eager to liberate themselves from their overlords, the Aztec, who demanded not only precious materials, but also regular human sacrifice from the conquered tribes. In addition, Cortés was fortunate to land where several survivors of previous Spanish expeditions had married local women. It was auspicious that he was given an intelligent indigenous slave woman, La Malinche, who converted to Catholicism, bore a son for Cortés, and became his trusted interpreter. She spoke several native dialects and quickly learned Spanish. Some Mexicans revile her as a traitor.

He created a local government and conspired to have himself elected El Magistrate, making him responsible only to the king. Cortés wrote five short letters to the Spanish king in which he explained his actions and informed the king about the indigenous peoples, their barbaric ways and justifying the brutal subjugation of the heathen population.

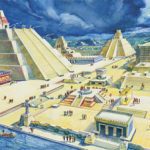

November 8, 1519, nine months after sailing from Cuba, Cortés and his followers, including 1,000 Tlaxcala, were reluctantly granted permission by Montezuma to enter the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, a city of over 400,000, was constructed on several islands in a lagoon and was described as more beautiful than Venice. The Spaniards and their allies were not welcomed by most of the city’s inhabitants; however, Montezuma provided the Spaniards with quarters and food.

Soon Cortés began to have precious Aztec religious and decorative gold objects melted and cast into gold bars weighing 4.35 pounds each, which were intended for the Royal Spanish Treasury, in Madrid. Cortés had some of the bars shipped to Spain. The vessels stopped in Cuba where the Spanish inhabitants learned of the Aztec treasure. Several of the ships carrying Aztec treasures were lost in transit, however. It is conjectured that the majority of the gold bars disappeared when Cortés and his men, many weighed down with gold bars, fled the Aztec capital on the night of June 30, 1520. The Spanish called this The Night of Sorrows, La Noche Triste. The flight from Tenochtitlan was a crushing blow. Bernal Diaz wrote that Cortés wept at the loss of his men.

Several weeks before La Noche Triste Cortés left the Aztec capital in charge of Pedro de Alvarado, who like Bernal Díaz had sailed with Grijalva. Cortés travelled to Veracruz to convince the nephew of Cuba’s governor, with his nineteen ships, 1,400 soldiers, twenty cannons, 80 horsemen, 120 crossbowmen, and 80 harquebusiers, not to arrest Cortés, but to join him in conquering the Aztecs and enriching themselves, as well as the Spanish crown. While Cortés was away, Alvarado took advantage of his appointment and ordered the slaughter of several thousand Aztec priests, nobles and citizens by trapping them in the large Patio of Dances as they euphorically participated in the Serpent Dance. To restore calm after this slaughter, Montezuma was forced to speak to his people from a rooftop. Bernal Diaz wrote that during his attempt to restore peace the Aztec emperor was struck in the head by rocks thrown by an angry crowd. Some say the mob was led by his nephew and son-in-law Cuauhtémoc. Later accounts claim the emperor was murdered by the Spanish. Montezuma was replaced by Axaycactl, his 19-year-old son, who ruled for less than three months before dying of smallpox, which left Cuauhtémoc as emperor of the Aztecs. He proved to be a fierce defender of the Aztec people, their capital, and their beliefs.

Nearly a year after fleeing the Aztec capital, Cortés returned with his larger army, plus 100,000 Tlaxcalan warriors and determination. The fierce battle for Tenochtitlan lasted 93 days. Cortés had wanted to preserve the beautiful Aztec city. However, because the Aztec warriors used the city’s buildings as fortresses and places to ambush and defend their capital, Cortés found it necessary to dismantle each structure as it was captured. Cuauhtémoc would not have capitulated except Cortés had managed to block the supply of food and fresh water; plus the Aztec were overpowered by the superior Spanish arms, the Tlaxcalan warriors aligned to the Spanish and by smallpox. As many as 240,000 Aztecs died and an estimated 40,000 corpses floated in the shallow lake. Almost all of the Aztec nobility had died, leaving mostly young women and children. Even after the surrender the Spanish allies, the Tlaxcalans, slaughtered survivors. The Spanish soldiers and their allies had fought as if possessed because captured soldiers were sacrificed at nightly rituals by the Aztec priests.

Bernal Diaz writes that the Spanish soldiers barely slept and when they slept they did so wearing their armor; they were kept alert for attacks by the constant beating of drums. The soldiers could not sleep for long because of the screams of their captured comrades as their bodies were ripped open by razor sharp obsidian knives and their still beating hearts held aloft as sacrifices by the Aztec priests. Diaz writes that the Spanish could often witness the gruesome death of their comrades.

After his capture Cuauhtémoc was the prisoner of Cortés for two years as they marched south in search of still more gold and souls. Cortés was convinced by one of his adjuncts that the prisoner Cuauhtémoc was plotting a rebellion so that he could once more rule the Aztec people and reclaim the Aztec wealth and restore their gods. Cortés had Cuauhtémoc and Tetlepanquetal and the Tlatoni of Tlacupan tortured and hanged until dead. To Bernal Díaz this brutal act seemed deranged, although he had been a defender and friend to Cortés from the beginning. The torture and death of Cuauhtémoc terminated the bond between Cortés and Bernal and elevated Cuauhtémoc to the status of hero.

Today Cuauhtémoc is the fortieth most popular name in Mexico; there are more streets, monuments and areas named for the last Aztec ruler than there are for his famous uncle Montezuma.

For more information about Lake Chapala visit: www.chapala.com

- Mexican Streets - October 31, 2023

- Princess Agnes Made a Difference - July 30, 2023

- MEXICANS AND MEXICAN AMERICANS:Remarkable Lives and Unforgettable Stories - June 28, 2023