He clicked the scissors twice. On the first click, my stomach clinched, but on the second, I felt something break—like a tight rubber band. I didn’t look in the mirror to see the first lock fall to the floor, but by the second cut, I was ready to face facts. I looked to the floor where two eight-inch-long tendrils curled cozily entwined, spooned like lovers on a bed.

What was he removing from me, this pert young man in tight pants? Was my power in my hair, or my sexuality? When he went to answer the phone, I bent over and picked up one of the strands, trying to read it like the rings on a two-thousand-year-old tree. This inch nearest the cut was probably growing out of my head, just making its first appearance, during Bob’s final months.

How much pain had that hair been infused with? How much silence? How many words unwisely spoken? How many words held back? Why was that inch not curlier and thicker? Why didn’t it display the strength I’dfound in myself during the period of his dying that I hadn’t even known I possessed?

As Alejandro returned from the phone and resumed his task, I let the lock fall to the scuffed floor. The aged grain of the wood and flecks of paint gave an aura of age to the pile of locks which rapidly grew to blanket it. This was the hair I’d pinned to the top of my head as we labored together to empty our old house, to close down our studios and to pack the van for our move to Mexico.

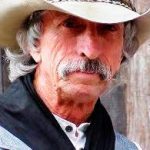

Bob had liked my hair long, uncurly, natural—matching his own wild mane. When I was young, my hair had been my glory, and by keeping it, I’d tried, perhaps, to keep my youth. But now it was as though each snip snipped off that many years. Snip went the exhausting months of selling off all of our household goods in preparation for our move to the house we’d bought in Mexico. Snip went the dismantling of Bob’s eighteen-foot steel sculpture as his oldest son carried it away. Snip snip snip. Onto the floorboards fell a houseful of memories sold off to become parts of other people’s lives. Snip. The long-locked hand-carved wooden Rangda mask we’d bought in Bali. Snip. The last of our handmade lamps. Snip snip, the mask from the Berkeley flea market. Snip. The studios full of tools, the bins of screws and nails. Snip Snip the twelve-foot-long diamond saber saw made by Bob’s own hands with castoff parts from Lawrence Livermore Laboratories. Snip. A lifetime of papers cast on the dump heap: old teaching files, tax forms from the seventies. Boxes of chapbooks, journals, old letters.

Snip went the slow loading of the van with the remaining possessions that would go with us into our new life. Snip went the doctor’s hard news just days before we would have made our escape from our past life and our journey into our new life in Mexico.

Snip went those weeks of single-handedly nursing Bob at home. His death. His memorial. The long drive down to Mexico with his ashes in the toe of his kayak still lashed to the top of the van. Snip went my first year alone as I labored to repair and fill the empty house I’d thought would be ours.

Finally, Alejandro puts down the shears and begins to blow dry my hair, running his fingers through it to the roots—the most sensual experience I’ve had for a year. He turns off the dryer and I look in the mirror at a woman twenty years younger.

“I must have you,” I tell this woman, “I must have your carefree demeanor, your unencumbered life. Your freedom, your simplicity.”

“You done,” says Alejandro, clicking off the dryer and spinning the chair to give me a better look in the mirror, cutting me off from the past three years. Giving me her.

- Permanent Bond - February 29, 2024

- A Strange Touch - January 31, 2024

- There is Always Music - December 28, 2023