The Renegade Spaniard

By Mildred Boyd

It was hardly a safe haven. The group was immediately surrounded and taken prisoner by the local Maya. Some were sacrificed almost immediately; the rest were put in cages to be sacrificed later or sold as slaves. A few escaped into the interior only to be enslaved by other, though less bloodthirsty, masters.

In 1519, when Cortez reached the island of Cozumel and heard rumors of enslaved Spaniards on the mainland, he sent a boat with soldiers and a small “fortune” in the colorful glass beads so prized by the natives. They were ordered to either rescue or ransom the captives.

Sadly, after eight years, only two men were still alive. One was the priest, Geronimo de Aguilar, who had remained a slave and true to his vows of celibacy, had never taken a woman. He gladly accepted the beads, bought his freedom and hastened off to where Gonzalo Guerrero was living, bearing the good news and more beads.

To his astonishment, Guerrero, who had actually fared much better in the Mayan society, declined being rescued! Although Cortez fails to mention the second man at all in his dispatches to the Charles V, gossipy old Bernal Diaz del Castillo’s True History of the Conquest of New Spain reports Guerrero’s arguments in great detail. “… I am married and have three sons. The Indians look on me as a chief and a captain in wartime.” Adding, “… my face is tattooed and my ears are pierced. What would the Spaniards say if they saw me?”

Guerrero’s wife interrupted asking angrily, “Why has this slave come here to call my husband away? Go off with you, and let us have no more talk.”

Aguilar argued a little more, reminding him of his Christian faith and the danger to his everlasting soul but Gonzalo was not to be convinced. In truth, there was no reason why he should have been. The man had sense enough to know that he was far better off than he could ever have dreamed of being as a common sailor with only back-breaking toil and a watery grave for a future.

He had married the daughter of Nacham Chan, the Chieftain of Chetumal. In so doing he had become a wealthy aristocrat in his own right and the nakum (captain) of the tribe. Furthermore, he had already committed treason in the eyes of his compatriots by teaching potential enemy warriors Spanish fighting tactics and how to defend themselves against guns and steel weapons.

Perhaps he was wise not to add that he knew very well that the Spanish would call him a traitor. When Aguilar reported that Guerrero had led the Maya attack against Cordoba’s vessels the year before, Cortez prophetically replied, “I wish I had him in my grasp! It will never do to leave him here.”

Aguilar, after some trials and tribulations, rejoined his countrymen and, having learned the Mayan language during his captivity, served Cortez well as translator until they reached lands where only Nahua was spoken. Marina, the slave girl Cortez later acquired, did speak both tongues and, until she learned Spanish, the awkward three-way translation worked well.

Guerrero, however, disappears from the history books only to surface again some years later in the rumors of a mysterious white man leading the lowland Maya warriors into battle against groups of armed and armored Spaniards—and winning! Years later, serious expeditions were mounted to conquer the Maya.

In June, 1536, a bearded, tattooed foreigner dressed as a Mayan warrior was found among the dead after a battle between Pedro de Alvarado and a local Honduran cacique. The man, killed by a harquebus shot, was assumed to be Guerrero, who had come to the aid of the cacique with thirty canoes filled with warriors.

Some historians have claimed that he never existed, at least not as the romantic traitor/hero of the stories. There seems no doubt that a sailor named Gonzalo Guerrero did sail on that ill fated voyage but everything else, they claim, is nothing but hearsay. Aguilar could have made up the tales damning Guerrero if only to emphasize his own loyalty in answering Cortez’ summons.

The Spanish could have manufactured the stories of a white renegade war leader to excuse their own poor showing against pagan Maya forces. They make much of the fact that Guerrero’s name never appears in Mayan records though it would hardly be surprising if he had adopted a new name more fitting to the society he had embraced.

True, there is no evidence from Guerrero’s own hand to confirm the story, but it is documented by others. Cortez, Diaz, Oviedo and other contemporaries wrote of him. Francisco de Montejo even entered into correspondence of a sort with him. When, during his first Yucatan campaign he discovered that Guerrero was the ruler of Chectumal, he tried to woo him with a longish letter offering friendship and a complete pardon. Guerrero replied, writing on the back of Montejo’s letter, that he could not leave his Lord because he was a slave and mentioning his obligations to his wife and children. Later chroniclers depicted him as the worst of traitors if not the devil incarnate.

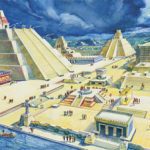

The people of mixed blood, who make up the majority of Mexicans today, have no doubts. To them, Gonzalo Guerrero is a cult hero and he and his Mayan spouse, Zazil Ha, were the progenitors of their race. In 2005, the people of Akumel, which he supposedly founded, erected a statue of him as “Padre de Mestizos.”

- April 2024 – Issue - March 31, 2024

- April 2024 – Articles - March 31, 2024

- April 2024 - March 31, 2024